Hi, we're Ella and Rob

Rob is a team-oriented, creative, passionate, responsible full-stack developer who likes inventing new things and making the world better.

My favorite book is 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

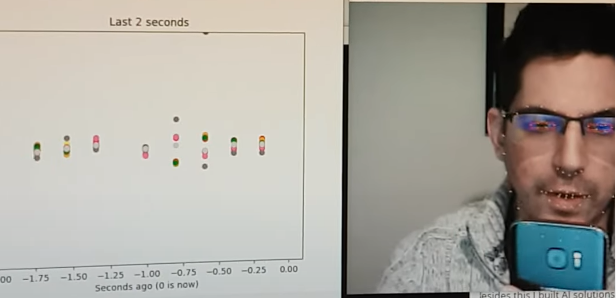

Me working on gesture recognition software in Python, demo here.